Dear everyone,

Sitting here on this rainy eve in NYC on my medium-pile rug...

I was going to play Animal Crossing because I worked a lot today… and I’m tired… but instead I thought I’d send along some ongoing reflections on the topic of death. Hopefully it's not too heavy.

I’ve been noticing where life and death sit comfortably with each other… the ability of the presence/prospect of death to enhance life… and then, with that thought in mind, the act of intentionally building death into a life.

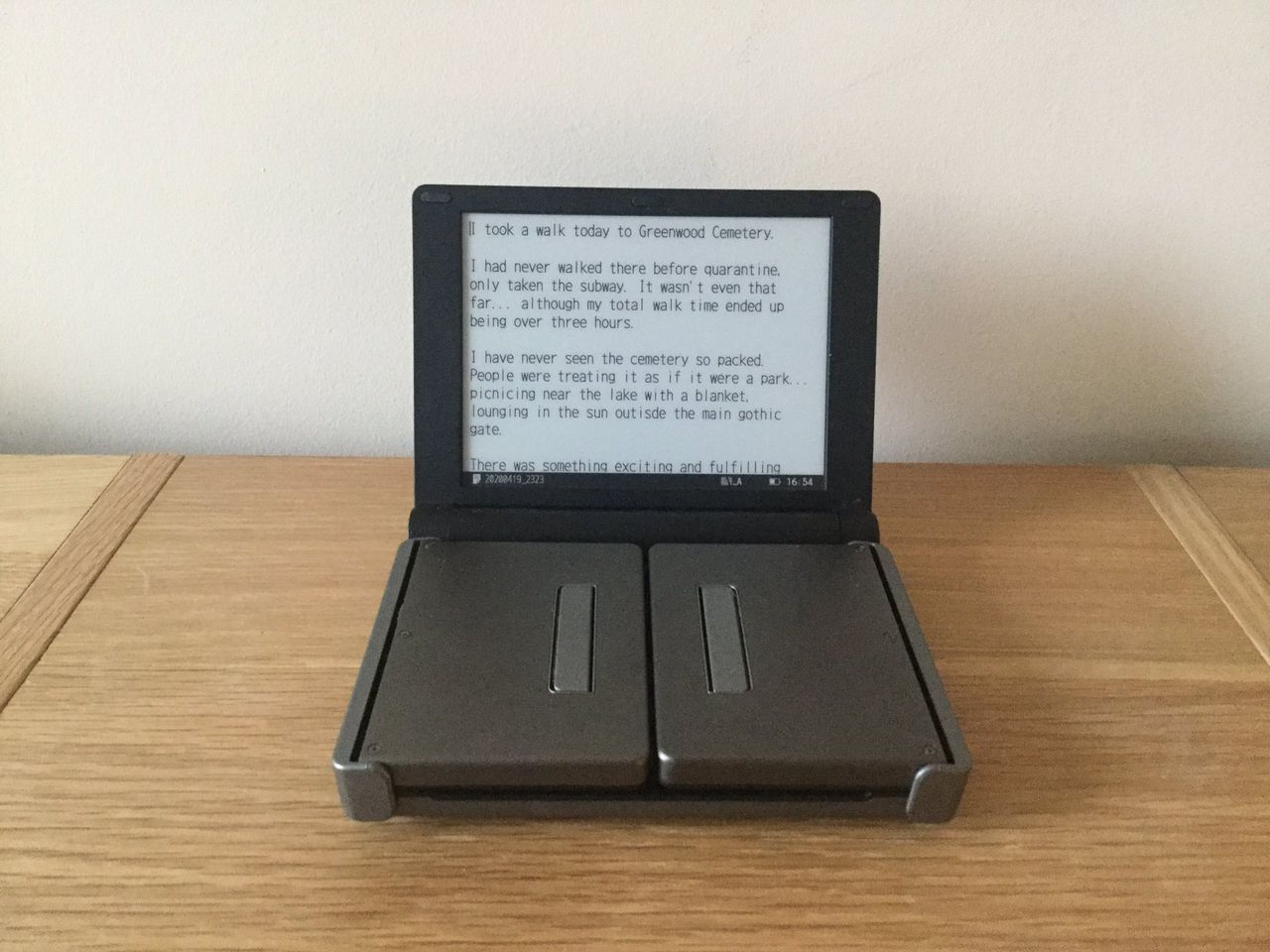

I recently took a walk to Green-Wood Cemetery.

I had never walked there before quarantine, only taken the subway. It wasn't even that far... although my total walk time ended up being over three hours.

I had never seen the cemetery so packed. It was a beautiful sunny Sunday. People were treating it as if it were a park... picnicking near the lake with a blanket, lounging in the sun outside the main gothic gate.

There was something exciting and fulfilling about noticing this. It feels healthy for life and death to be intertwined. I remember walking around the countryside of Japan this past summer, marveling at how tiny cemeteries cropped up often, amidst other regular buildings and zones. They were small and felt sprinkled about. Our cemeteries typically are so far apart. They often feel like huge, isolated worlds due to contemporary urban planning. It's not often I "happen" upon a cemetery.

Ambient cemeteries…

I once found a fragment of text somewhere… “How many little deaths does it take to make you come alive?” A similar feeling permeated through the last perfume review I wrote… “Art at its wildest best is so wildly elegant, shocking yet subtle, that death is as present as life.”

I later found out via a kind internet friend that since Green-Wood Cemetery opened in 1838, before either Central or Prospect Parks, it stood out as one of the first publicly landscaped sites in NYC. So back then, it was used by New Yorkers much like the big parks are used today…

I haven’t experienced much death personally yet. I feel lucky but also afraid.

Sometimes, as a sort of drill for myself, I imagine what it’d be like for a close friend or family member to die. I do this while in the shower… a private place where crying is easy. And the shower is where expansive thoughts are welcome (#showerthoughts). It feels strange to relay this to you—but I’m doing it because I’ve found it a helpful activity... Not that I expect it to really prepare me… I have no idea what that will be like. But somehow it feels healthy. As water rushes over me, I think about how death of this special person would change me and what I’d do… both from an emotional and pragmatic standpoint.

Memorials are often static. They may be fixed places of grieving or contemplation; a wall, a fountain, a statue.

Instead, a social network for the dead: a bit morbid; but at the same time, what’s more alive than a regularly updated Facebook profile? Mourning is already done online; entering a lost friend or family member into Google’s search bar is a plea to be reconnected. Browsing online creates a momentum of discovery: grief is research. Here grief can be experienced as a shared thing, part of a transcendent, even celebratory movement.

The YAMP website officially launches today. If you go to yamp.org, you’ll see that it starts as a long paragraph filled with various colored and underlined words. The paragraph is made up of sentences: each sentence is a mini biography of a member of the Yale community who died of AIDS. You don’t have to click anything here, but there are many things to click: the site is a memorial built from a hypertext weave. Clicking links that correspond to Yale colleges, majors, activities, images, locations, dates, and places, you can begin to see AIDS at Yale as an epidemic that impacted a diverse, interconnected, and specific community; as well as a series of individual losses. As more profiles are added to the website over time, this network becomes both denser and broader.

The oxygen of YAMP is this hypertext.

The above are excerpts from "Electric Memorial", my writing from 2013 when announcing the launch of yamp.org, the Yale AIDS Memorial Project. I was its lead designer back when I worked at Linked by Air. I feel really lucky and honored to have worked on YAMP, as the project truly utilized the type of design we did for a most meaningful purpose.

Through simply its medium of website, YAMP was more of an ambient cemetery, although you still had to go out of your way to “visit” it.

Recalling YAMP reminded me of the power of names…

I once called a name a “poem in the wild” when I gave a workshop about generating new names.

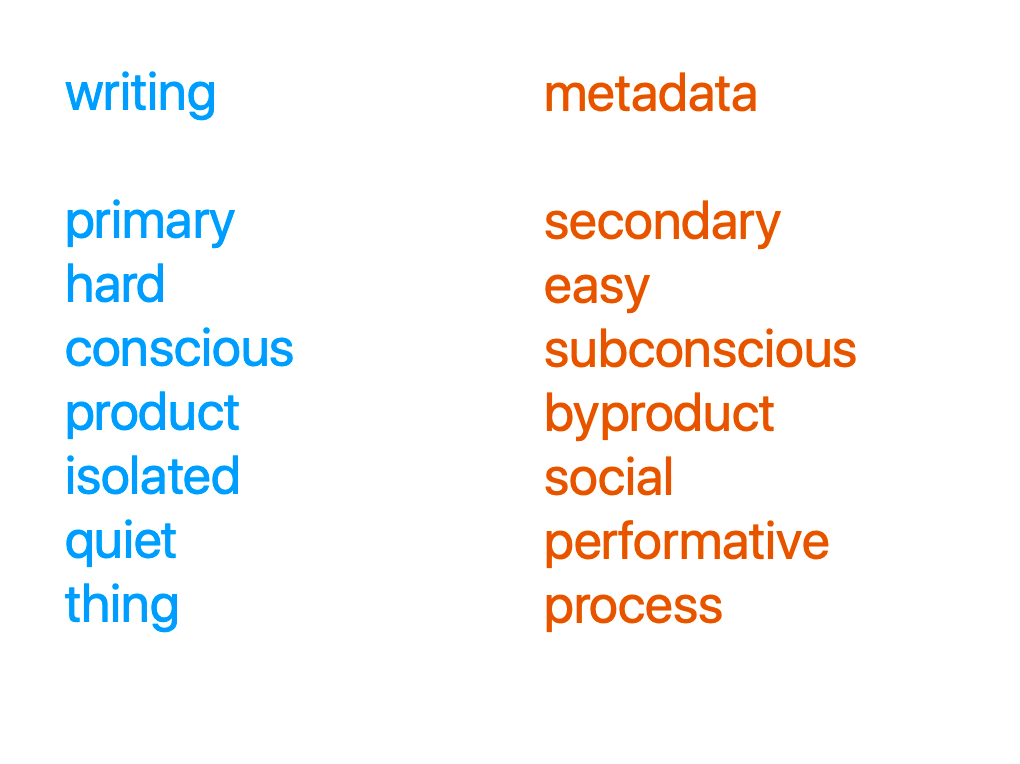

I talked about this and related topics in “Writing as Metadata,” a class I taught last year at Yale…. The idea is that the life-force (of a work) really lives in its metadata, the subconscious and secondary parts, which are often “wild” in that they circulate or roam about.

I described that the true nature of any work is a combination of its content and its metadata. Its metadata could be… anything about the work… its documentation… the story you tell about it… the way people talk about it.

Now that I think about it, maybe this is how names work and are activated.

Maybe once or twice I’ve given my Yale classes a reading by artist Maya Lin. I couldn’t help but find the coincidence meaningful… that she was also at Yale. It was in the 70s she designed the Vietnam War Memorial as a student in a class on funereal architecture, which studied how people, through the built form, express their attitudes toward death. In her reflecting on designing the memorial after much time had passed, in the year 2000, she described her own relationship to names:

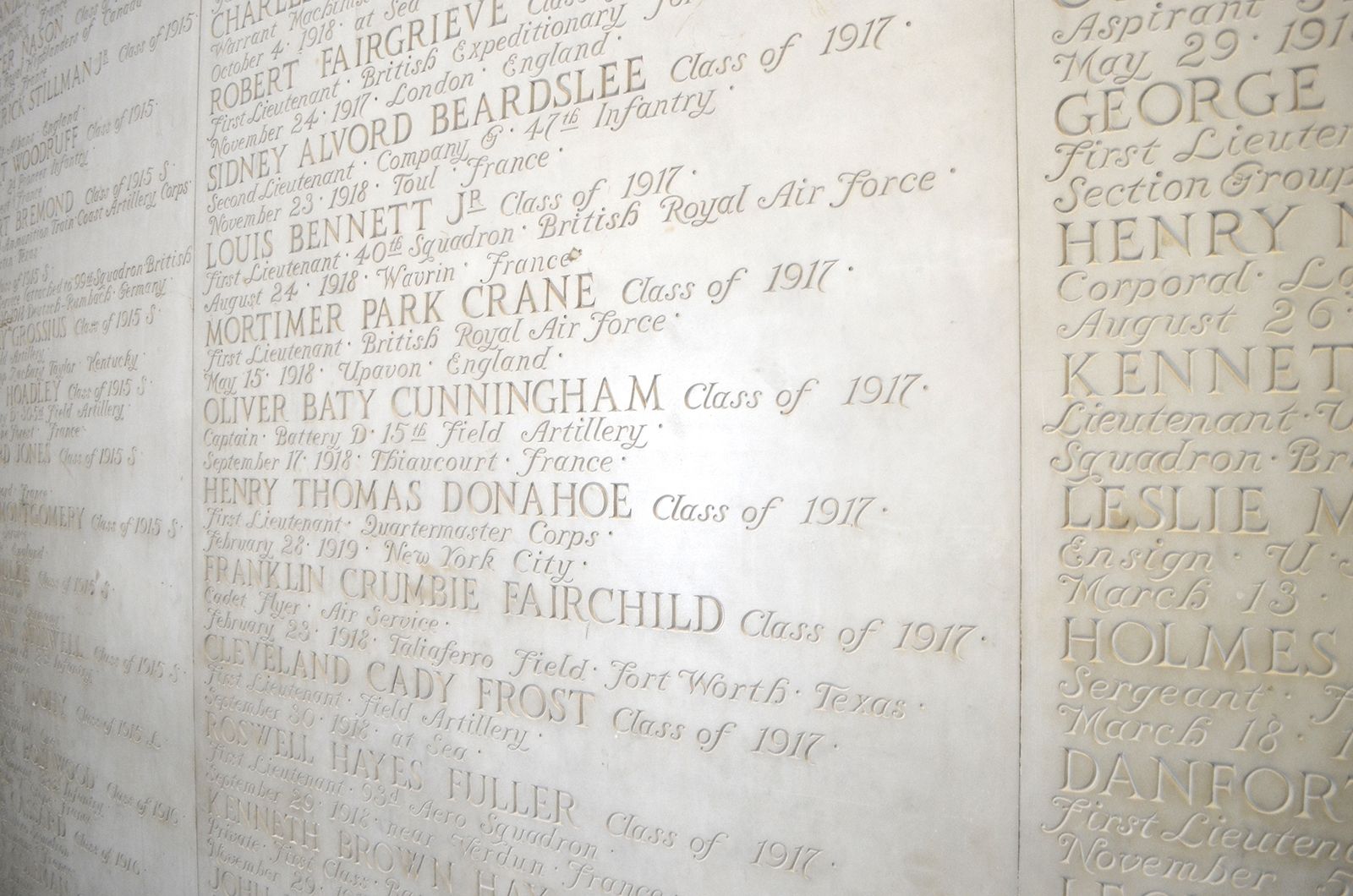

In Woolsey Hall, the walls are inscribed with the names of all the Yale alumni who have been killed in wars. I had never been able to resist touching the names cut into these marble walls, and no matter how busy or crowded the place is, a sense of quiet, a reverence, always surrounds those names. Throughout my freshman and sophomore years, the stonecutters were carving in by hand the names of those killed in the Vietnam War, and I think it left a lasting impression on me…the sense of the power of a name.

I wanted to focus on the nature of accepting and coming to terms with a loved one’s death. Simple as it may seem, I remember feeling that accepting a person’s death is the first step in being able to overcome that loss.

I felt that as a culture we were extremely youth-oriented and not willing or able to accept death or dying as a part of life. The rites of mourning, which in more primitive and older cultures were very much a part of life, have been suppressed in our modern times. In the design of the memorial, a fundamental goal was to be honest about death, since we must accept that loss in order to begin to overcome it. The pain of the loss will always be there, it will always hurt, but we must acknowledge the death in order to move on.

What then would bring back the memory of a person? A specific object or image would be limiting. A realistic sculpture would be only one interpretation of that time. I wanted something that all people could relate to on a personal level. At this time I had as yet no form, no specific artistic image.

The use of names was a way to bring back everything someone could remember about a person. The strength in a name is something that has always made me wonder at the “abstraction” of the design; the ability of a name to bring back every single memory you have of that person is far more realistic and specific and much more comprehensive than a still photograph, which captures a specific moment in time or a single event or a generalized image that may or may not be moving for all who have connections to that time.

Then someone in the class received the design program, which stated the basic philosophy of the memorial’s design and also its requirements: all the names of those missing and killed (57,000) must be a part of the memorial; the design must be apolitical, harmonious with the site, and conciliatory.

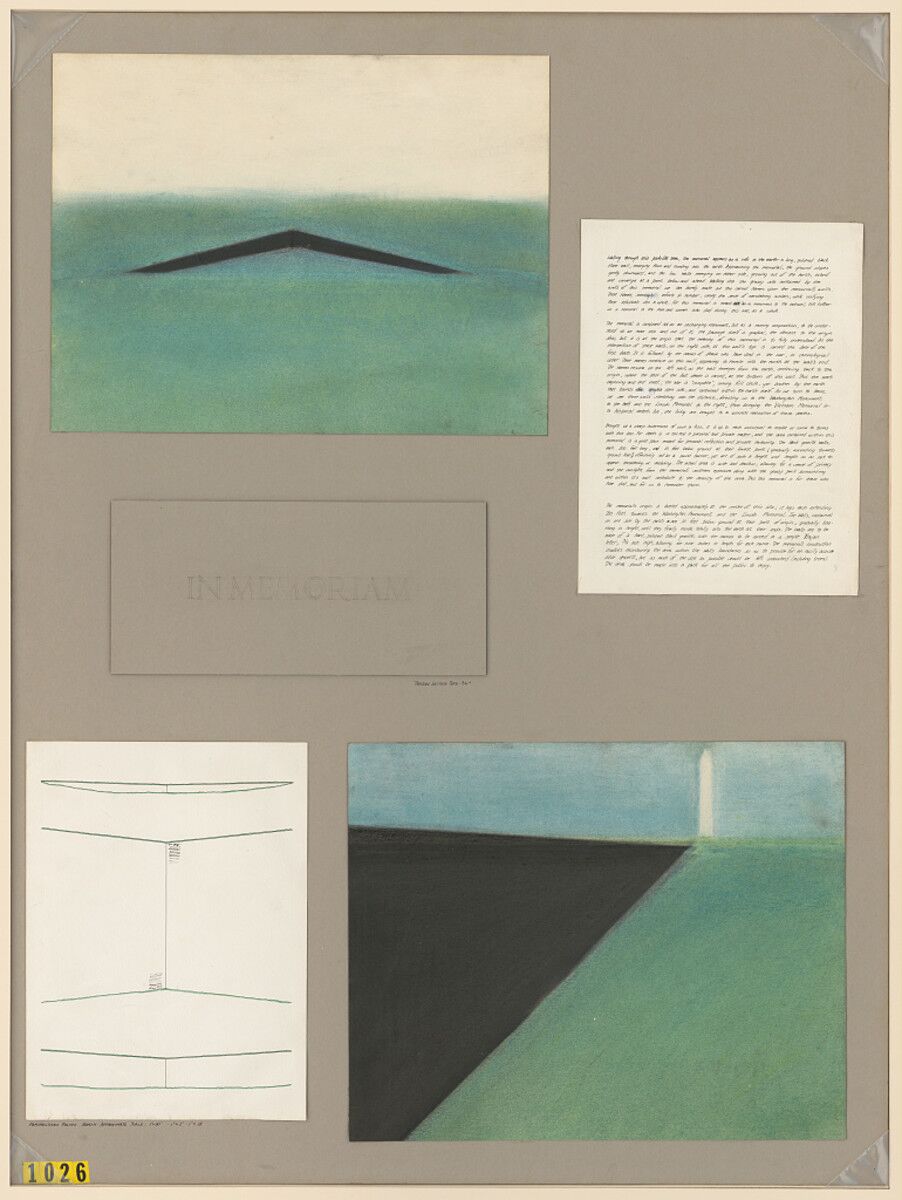

I had a simple impulse to cut into the earth.

I imagined taking a knife and cutting into the earth, opening it up, an initial violence and pain that in time would heal. The grass would grow back, but the initial cut would remain a pure flat surface in the earth with a polished, mirrored surface, much like the surface on a geode when you cut it and polish the edge.

The need for the names to be on the memorial would become the memorial; there was no need to embellish the design further. The people and their names would allow everyone to respond and remember.

It would be an interface, between our world and the quieter, darker, more peaceful world beyond. I chose black granite in order to make the surface reflective and peaceful. I never looked at the memorial as a wall, an object, but as an edge to the earth, an opened side. The mirrored effect would double the size of the park, creating two worlds, one we are a part of and one we cannot enter.

As I talk about weaving life and death, it would be a mistake not to mention Mexican tradition and attitudes towards death. My mom told me how in Mexico, people die “three deaths”: The first is when the heart stops beating and the body stops functioning. The second is when that body goes into the earth. And the third death is the last time someone speaks that person’s name aloud… when there is no one left to remember that person.

Maybe names of the dead are the true ambient cemeteries. And their power to be interacted with by the embodied living—touched by hand, like those engraved in stone, or spoken aloud with the voice, by those remembering, is the true portal from our earthly realm to the one beyond.

2020/04/19 23:23

Thanks to Meg Miller for reading and responding to a previous draft of this reflection.

Sending peace,

Laurel

This is Laurel's "Reflections" newsletter 🎐.

If at any time you’d like to unsubscribe, or subscribe again, you can do so at:

http://email.laurel.world.

The username is writer and the password is thoughts_become_things.

Thank you for receiving this transmission.